“Look at that red Tesla, it looks really nice, doesn’t it?” I said as we pulled out of the school parking lot after Hugo and Celeste’s after-school tennis lesson.

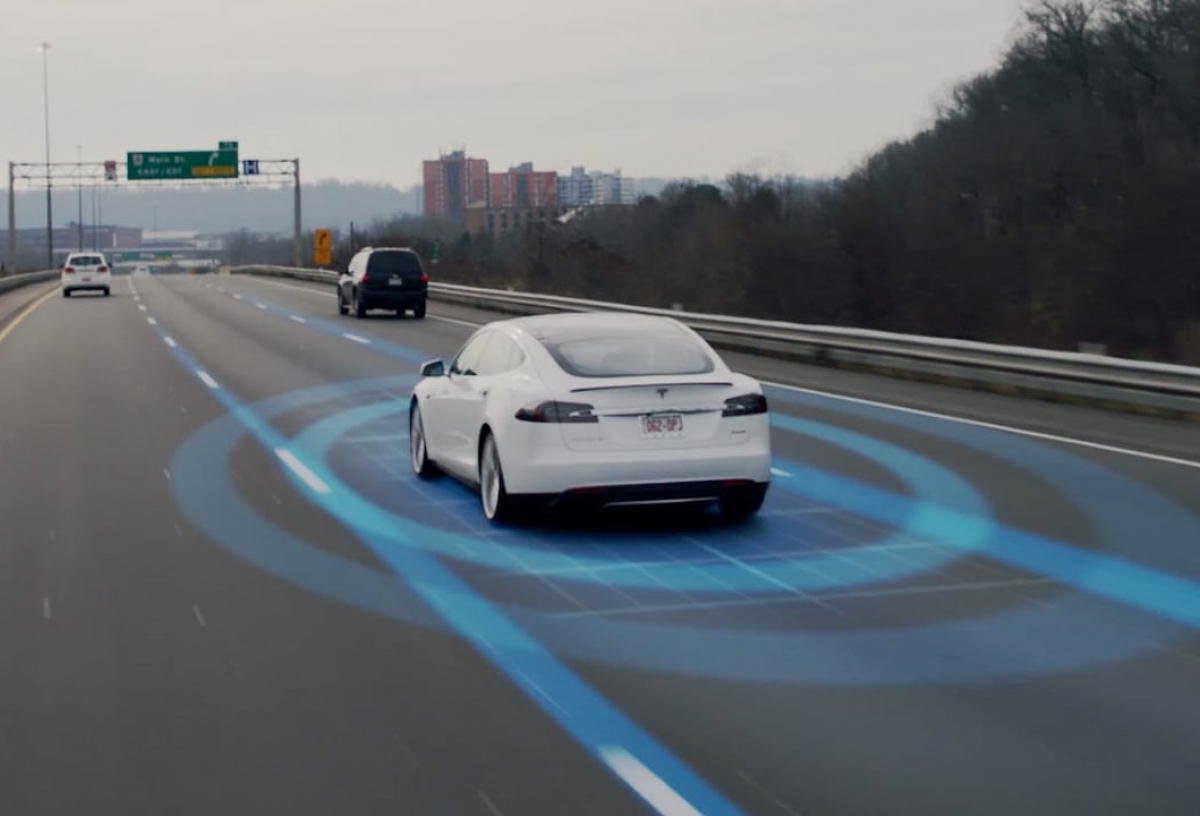

“That’s Claudia’s car. It is so cool, it drives by itself,” said Hugo impressed by the fact that somebody else’s car was better than daddy’s.

“Yes, you tell it where to go, and the car just takes you there,” added Celeste, proud to know how Tesla cars work, as she was the only one who had been inside Claudia’s Tesla.

Silence for a second. “Can you use Nexar to drive the car?” asked Hugo curiously.

“No, not yet. You will one day,” I said in a very easy manner, not quite knowing what was coming ahead.

“Wow, cool. So I will be able to drive the car using the iPhone from the back seat!” Hugo added whilst jumping out of his booster seat in excitement.

“Sit down, Hugo. Well, no, not quite yet. It is not like a game, and you will not be able to remote control the car using the iPhone. It is more like Nexar will have a brain that can make decisions as of how to drive,” I clarified for him, after which he seemed rather puzzled and definitely disappointed.

Taking a positive twist, Celeste finally asked me “when will Nexar drive the car?”

“It will take a while,” I replied trying to bring an inspiring tone.

“Why? Can’t you just program it? That’s what the Tesla does. It’s like Waze. You enter your destination and then the car knows where to drive,” inquired Celeste a second time, as I took a right turn onto St Julian’s Drive.

“There is more to it than the car knowing where to go. The car needs to know also how to drive, and how to deal with things it has not seen before,” I tried to clarify. It was starting to be clearer that they were not understanding why navigating a car was so different than driving safely as their dad was trying to tell them.

“How does the car know how to drive?” asked Hugo, trying to grok what I was saying.

“You teach it,” I said, in what came out in a rather mysterious tone trying to spur their imagination.

“And how can you teach it!?,” inquired again Hugo, getting more excited by the second about the prospect of teaching a car how to drive.

“Just like you code on Scratch or Logo, you program the car to steer, accelerate, brake …,” I added, hoping the analogy would come through and that they would understand the need to carefully deconstruct the problems.

“And it knows where to go to, so that’s all easy then,” said Celeste, downplaying the importance of safety. Since the car knew anyway which route to take, it can’t be that hard, can it?

At this point I tried to see if going into more detail would clarify things, “well, yes, you can write a simple program to drive and avoid things on the road. But for driving in the real world you need more. Remember sometimes your programs on Scratch don’t work like you thought they would?”, finally I felt sort of satisfied that perhaps this approach would help me clarify the difference to them.

“Yeah,” they both asserted. Victory! Or so I thought, and went on to add further detail. You know, the fatherly thing.

“Well, in those situations when programs don’t work as expected, we say that they have “bugs”. “Bugs” are things you not plan for properly as you wrote the program code, and the computer as a result makes errors. When you are driving, those errors are critical, since if you make an error, the car may crash and kill people,” I added. I felt we had finally called out the complexity of driving safely.

“Daddy, can YOU write the program for the cars to drive?” enquired again Celeste. How do you answer this? Obviously, I can’t, but what father wants to disappoint their children?

“It takes a team of really good people, and a lot of real-world driving examples for learning how to drive,” I decide to answer in order to highlight the complexity and time it takes to teach a car how to drive.

Celeste was obviously concerned, but not disappointed. “How do you know there are no bugs left? What if there is still an error?” she asked.

“You need to improve your program, and get more examples for learning,” I clarified.

“But that will take for ages! Can’t you do it faster?” interjected Hugo, with a classic impatient boy question.

“Yes. We can. That’s what we are doing at Nexar,” I tried to add, hoping that would settle it.

“Cool. How?” Celeste asked. Okay, I thought I was done, and this is getting tougher now again. What’s going on? Let’s try again to answer.

And so I went, “well, first we start with the basics, where making an error has less of an impact. For example, warning you of an accident ahead.”

“Yeah, like the Tesla. It can send you in a different way if there is an accident ahead, because it knows where you are going to,” contributed Celeste.

“True,” I said. This time it had clicked. I was trying to convince them of something that intuitively was wrong. And they had been right the whole time. Knowing where to go is the first macro decision to drive an autonomous car.

“And once you start with that, Nexar is effectively the co-pilot, and is continuously learning how to drive from the backseat. Just like you do watching us drive.” I added, switching to expand on their initial thinking.

“So, you can then teach Nexar to recognize a horse blocking the road, slow down and pass slowly on the side?” Hugo asked, sort of coming to next logical conclusion by himself.

“Yes, or take a detour to get faster to the destination,” added Celeste at this point, excited they were onto something big.

“Yes, and you drive and more in co-pilot mode, slowly you learn more and make less and less errors. The more you drive, the more you learn, that’s the key for how we are approaching this at Nexar. At some point you have learnt a lot and you are confident you can start driving and controlling the car,” I added, satisfied we were getting somewhere.

After a brief silence, Hugo asked, “what if there is still a bug? Can’t you write the program without bugs?”

“There will always be situations when the computer does not know what to do. Nexar will then ask the driver for help,” I clarified.

“So, the car can’t always go by itself,” summarized Hugo.

“No,” I confirmed.

To which Celeste quickly interjected reassuring us we were right, “yeah, I think the Tesla does not do that either.”

“Exactly,” I said.

At this point, Celeste felt compelled to tell the story, “so one day, soon, with Nexar running on the iPhone, we will be able to drive the car. It will ask you where you want to go and then know how to drive and which roads to take to get there safe and fast.”

“Yup. That’s it. You got it,” I closed, happy about having picked up today the twins from their tennis lesson.

“Let’s start building program that drives the car on Scratch when we get home,” added Hugo in excitement, as him and Celeste started to dream about phones driving cars driving by themselves.

blog comments powered by Disqus